Lies, Damned Lies and Archives.

i

The past is fragmented and falsified. Of course, this is nothing new. Archives have been doing this since the concept of archive was first mooted but if, as a result of this constant real time revisionism, all we remember is false, are we not contributing to our own psychological entropy?

Academic archives, at least, tried to illustrate a flow of time and thought even if that was subject to societal and personal preference. Archives, physical or the unruly online deluge, act as humanity’s id, and the unbound id inevitably leads to destructive pandemonium.

Can one truly remember ones past when there is such a capacity and clamour to edit, filter and manipulate the product of a camera that cannot lie? Archiving is a method of containing the past, of freezing time to study later. How, then, will we understand our own history if the archives we curate contain actively false information? How does this built-in inauthenticity affect George Santayana’s maxim ‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.’ (Santayana, 1998)

People have become their own archives, particularly with the rise of social media. Each moment, each breath, each meal, and purchase are catalogued in an open repository. Even this information is filtered to give the best possible – and often wildly inaccurate – impression.

Agoraphobia exacerbates this kind of revisionism, with each memory becoming fluid and subject to hyper-scrutiny. To rationalise one’s situation, the minutiae of past events become objects of obsession, sometimes at the expense of the memory that surrounds them. Past events are bloated or diminished at the whim of the psyche. Control of one’s personal archive slips and becomes tenuous. Time and memory distort, and Time’s Arrow loses its way.1

Reconstructing one’s past is not merely a phenomenon of social media, however. The curation of self has been happening forever. One always presents oneself in a socially acceptable way, changing to camouflage ‘difference’ and repressing those attributes that may extricate you from your chosen social group(s).

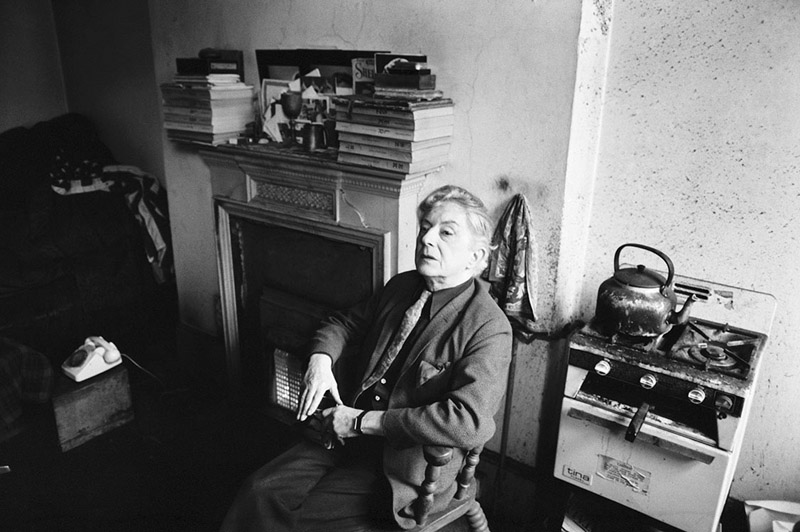

One of the most famous and extreme versions of this is the ego storm that created ‘Quentin Crisp,’ a character devised by Denis Charles Pratt. At the time, in the 1920s, homosexuality was illegal in the UK and an imprisonable offence. Offering a false name to the police served as a method of ensuring that the shame of arrest and the burden of guilt was not placed at the door of the family. Denis Pratt took on the mantle of ‘Quentin’, and the character consumed him to such a degree that when his biography, entitled ‘The Naked Civil Servant’ (Crisp, 1991) was filmed (Gold, 1975), his parents were referred to and credited as ‘Mr and Mrs Crisp’ and not Mr and Mrs Pratt. This misnaming is more of an acknowledgement than you might think, as neither of Crisp’s parents were mentioned by name at all in the book.

Quentin Crisp became a ‘brand,’ and his story became a ‘party line.’ Nothing came out of the Crisp camp unless it was vetted and rubber-stamped by ‘Quentin’ himself. He was essentially a ferocious guardian of his own archive, curating the character he had created to the extinction of Denis Pratt. He was operating as the raw data, processed data, storyteller, and mythmaker. To a lesser degree, we all do much the same thing, excising those things we dislike about ourselves and promoting those things we like, but rarely to the extinction of an entire persona.

How, then, do we trust an archive that is hermetically sealed by the subject of the archive? The answer is that with a lack of other information, we cannot. Derrida intimates that an archive is a living, breathing entity, (Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, 2017) so a hermetically sealed archive with no possibility of change is little more than the subject ‘lying in state,’ said subject fixing itself in time and in a kind of ‘deathless death.’

It is difficult to get any new sense of the man when biographers only have access to the Crisp curation of Crisp’s character. This means that of the several biographies available, the same quotes and anecdotes are regurgitated without critical discourse. In removing elements of his past that he deems inappropriate, discussion is made impossible except for those transgressions that were made in public – his comments on AIDS being ‘a fad’ and the quote ‘I regard all heterosexuals however low, as superior to any homosexual however noble,’ did him and the gay community no favours.

For the ‘regular’ person, the past is fragmented and falsified. Of course, this is nothing new. Archives have been doing this since the concept of the archive was first mooted, but if, as a result of this constant real-time revisionism, all we remember is false, are we not contributing to our own psychological entropy? Perhaps Crisp/Pratt has a point, although, from a man who once said he had ‘no interest in anyone else’ and ‘learned how to get attention at an early age’ if he wasn’t receiving it, often by faking illness or pretending to be upset, the value of such an archive is muted by the presence of an overwhelming ego.

An attempt was made at demystifying the idea of Quentin Crisp by his great nephew, Adrian Goycoolea, in his short film ‘Uncle Denis?’ (Goycoolea, 2010) that, according to the press release, ‘reflects on Quentin Crisp’s relationship with family and his family’s relationship with the idea of Quentin Crisp.’

Although interesting, it does little to get to the heart of Denis Pratt and, being only eighteen minutes long, speaks of a tightly regulated archive, even after Crisp and Pratt’s death(s). One may argue that Pratt died in the 1970s, of course, with Crisp rising, phoenix-like, from his ashes, but the fact remains that archives, especially such rigidly regulated ones, offer falsehood as well as truth to varying degrees.

‘One can give everything else away except identity,’ he said, ’that you must hold onto it for dear life.’ This would have more gravitas had he not thrown away his identity as Denis Pratt.

Academic archives, at least, tried to illustrate a flow of time and thought, even if that was subject to societal and personal preference. Archives, physical or the unruly online deluge, act as humanity’s id, and the unbound id inevitably leads to destructive pandemonium.

Agoraphobia, as mentioned before, exacerbates this kind of revisionism, with each memory becoming fluid and subject to hyper-scrutiny. To rationalise one’s situation, the minutiae of past events become objects of obsession, sometimes at the expense of the memory that surrounds them. Past events are bloated or diminished at the whim of the psyche. Control of one’s personal archive slips and becomes tenuous. Time and memory distort, and Time’s Arrow loses its way.

Archives serve a purpose, which is to contain the past. Like the ghosts in Ghostbusters and the creature containment facility in Cabin in the Woods, freeing those elements, either accidentally or on purpose, has had a detrimental effect on the acceptance of progress. The opening, the freeing of archives, has irreversibly stained us with the Janus Hue.

ii

Paul Klee’s painting’ Angelus Novus’ is one of the few hauntological touchstones that is not grounded in 1970s TV, movies or fin de siècle musical genres.

Walter Benjamin describes it thus: ‘It shows us an angel who seems about to iv. chain of events appears before us, he sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it at its feet. …But a storm is blowing from paradise and has got caught in his wings; it is so strong that the angel can no longer close them. The storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned.’ (Benjamin, 1970)

Once again, the simple, serene passage of Time’s Arrow’s A-to-B path is disrupted by past and future events. Benjamin acknowledges this by suggesting that history is not so much a ‘sequence of events like beads on a rosary’ – that is, Eddington’s cause and effect series – and behaves more like ‘a pile of debris, blown about by the winds of change.’ (Benjamin, 1970)

iii

I watched Ghostbusters2 on TV, not for the first time, and it got to the point where the Jobsworth official insists the ghost storage containment grid is shut down. The result is that the captured ghosts – slices of the past – are released into the present to become a signal for the end of times. Without melodrama or Luddite tone, this struck me as an interesting parallel to our currently available access to once occulted information.

Access to information has become a casual and passive pastime rather than an active quest for furthering knowledge. The internet has given us access to vast quantities of knowledge, the majority of which the average individual has no hope of understanding. If a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, the internet thrusts this danger into our faces, and the challenge to understand is taken up, often by those least capable of doing so.

Information from many disciplines is butted up against one another – with the aid of numerous hyperlinks that will inevitably take you off-topic – juxtaposing subjects that are incompatible or inconsequential. ‘I’ve done my own research’ is a phrase that fills me with dread. As much as I am a fan of William S. Burroughs and his ‘cut up’ technique. (Burroughs & Gysin, The Third Mind, 1975) It was never intended to be used as an academic tool and yet, removing sections from multiple disciplines and throwing them together in the hope of a coherent narrative – a forced narrative – is precisely what defines the concept of ‘post-truth.’

We live in a haunted world. The past, future and present bleed into one another. Information is stacked together, often in mysterious and unfathomable ways. ‘Context’ has become a thing of the past because of this ‘availability of everything.’ Anachronism has so become an intrinsic part of the now that it is not noticed, except to those who specifically look for it – and who often receive derogatory names because of it; geek, spod, anorak. The keepers of context are ridiculed. Anachronism is the zeitgeist. It is a zeitgeist that has slowly crept up on us and now pervades every moment of our lives.

Availability of information and anachronism have ensured that nothing is truly lost, Fisher agrees, saying that ‘in conditions of digital recall, loss itself is lost,’ but where once archives stored this ‘forgotten’ information, having constant accessibility to everything gives an entirely new texture to twenty first century living.

Pre-internet, information was stored and contained in libraries, galleries, museums, and other physical archives and had to be searched for. The past rarely intruded on the now unless one specifically looked for it. The passage of time continued ever forward but now we are consumed by the past, in thrall to the future and have somehow forgotten about the now. We live in temporal ‘negative space,’ wallowing in everything that is not now.

Once the province of academics, and at the risk of sounding elitist, this stored information is now subject to the untrained and undereducated for wild, uninformed misinterpretation that, repeated often enough, becomes ‘truth’ – this active repetition takes on a negative and damaging aspect.

But the archive is not sacrosanct and certainly not impartial, its contents having been curated by a series of archivists, each with a different idea of what information is deemed to be valid based on societal and personal preference at the time of construction. Archives are, therefore, not the unbiassed repository of cold and ‘set’ information they may appear. Rather they are a living and growing expression of human thought.

The opening of the containment grid at Ghostbusters HQ is analogous to the opening of cyberspace, a curiously archaic term that along with ‘the information superhighway’ has fallen out of fashion as the ubiquity of the internet became the norm; a technological marvel and an ephemeral space that contains more information about the past than we could possibly absorb. There is more contained within than an individual could possibly process and more contained than is empirically true. The contents are butted up against each other in no particular order and one can never be certain that the information it gives is true, false or conspiratorial half-truth.

The academic neatness of the archive has evaporated, and the walls of context demolished. Everything from the past and the present vies for equal attention and history manifests as a PC Monitor – transportable, distant, disposable, with its place in time uncertain. All of history is reduced to a handful of pixels.

Unexpected intrusions from the archive – real or metaphorical – were usually the province of the writers of ghost stories, M.R James (James, 2017) being a particularly eloquent proponent. Many of his stories involve an artefact that is out of place or time. This ‘out-of-time-ness’ often elicits a disruption to the neatness of academia. A more modern take on this idea can be seen in Joss Whedon’s ‘The Cabin In The Woods,’3 where an archive of monsters, used for the entertainment of elder gods, is unleashed after their tribute is not given.

The image of a row of horror movie icons – everything from Dracula, Frankenstein, and the Wolf Man to more modern horrors such as ‘It’4 and a creature that looks suspiciously like the ‘pinhead’ Cenobite from the Hellraiser movies (wielding a puzzle sphere, rather than a puzzle cube, presumably because of copyright limitations) – is startling. Each monster is seen trapped in a brightly lit, glass containment box, divorced from the shadows and the context that makes them so frightening within the movies. When the tribute is not paid, the glass walls come down and the once ordered archive becomes the embodiment of chaos.

This is obviously an image that fascinates Whedon. A similar set-up was used in season four of his TV show ‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer’5 in which a covert military operation, ‘The Initiative,’ attempts to capture and catalogue supernatural creatures, or ‘HSTs’ (Hostile Sub Terrestrial’) before attempting to weaponize them. Once again, rows of vampires, werewolves, demons, and the like are stored and decontextualised before the inevitable hubris-led id-storm. Like the ghosts in the containment grid in Ghostbusters, those slices of human time, removed from context and butted together, art galleries perform a similar function. A ‘white room’ designed to remove context and focus the mind on the work does not consider that the majority of pre- 1900’s artworks were created to enhance a specific space and perform a specific function. Portraits were not painted to be pretty, they were often commissioned to prove the wealth of the sitter, to intimidate visitors, to boast about ownership of land.

Taking these artworks out of their respective contexts and placing them in a sterile box, jostling for attention with other dispossessed artefacts does little service to the art works. Time and location are confused and confounded. There is little difference between this and the ‘parade of monsters’ seen in ‘The Cabin In The Woods.’

It’s interesting, then, that where vast tracts of information – previously only available to experts in their field – are now democratised and available to all, there has been a rise in anti-science, anti-vax, pro-religion at the expense of science, believers in the flat earth, conspiracy theories and theorists, the extremely distasteful notion of ‘crisis actors’ and most bizarrely a belief that Australia doesn’t exist.

iv

When scholars speak of ‘The Dark Ages,’ the term proves to be infuriatingly vague, with some declaring a span between c500-1400 CE and others saying that the completion of the Domesday Book is obviously the correct endpoint. As the term ‘Dark Ages’ indicates a time about which information is lacking, often non-existent, this raging about correctness seems entirely in keeping. The little that is known about that period is applied erroneously to the entire spread of up to nine hundred years. Time has been conceptually condensed. Innovations made at any point during this vast time span are applied to the whole period of this grossly inadequate term.

The Dark Ages present a problem. If the term applies to a period where little or no information exists, when documents, manuscripts, and relics are found, it splits the age into ‘ages.’ The Dark Ages become fragmented but are still perceived as a single span of time. Time’s Arrow, as perceived, glitches.

If the term ‘Dark Ages’ represents an era of scant information, what do we call the current time? The ‘Information Age’ seems woefully inadequate, such is the overwhelming volume, not only of information absorbed but information discarded.

In between is an era where the process of recording information, first in books, then audio, photography, and video, takes hold and expands almost exponentially.

Recording and archiving become less of an elitist occupation and more available to all.

The increased numbers of consumers demand more to consume, and with home recording equipment being made more readily available, personal archives are created and eventually shared for all to see. Of course, it also meant that personal archives in the form of recordings could be deleted, abandoned or otherwise destroyed. Modern technology, particularly the internet, is being treated as a kind of ‘information landfill.’

The most interesting point of this escalation for me is the point at which home recordings become available and accessible. The spaces between the Enlightenment and the birth of electronic information storage could be seen as a second Dark Age. The volume of available information is so poor, during this new dark age, compared to the minutiae of the modern person’s lives that are available for study and already in the public domain.

The cusp between this not-quite-as-Dark- Age and the post-internet era appears to be the starting point for hauntological study. Merlin Coverley suggests an even more precise and much earlier moment. That was the invention and implementation of the stage trick ‘Pepper’s Ghost’ in 1862. (Coverley, Hauntology: Ghosts of Futures Past, 2020) It is a simple trick involving a trap door, directed lighting and a sheet of glass, which allows for the projection of a spectral figure onto the stage; for the first time bringing a ‘realistic’ ghostly presence to the theatre. The invention itself comes with a level of haunting, having been invented by Henry Dirck and called ‘Dirck’s Phantasmagoria’ on selling the idea to John Henry Pepper, with the condition attached that his name be associated with the device, Pepper reneged. The device was marketed as ‘Pepper’s Ghost’ with Dirck’s involvement or invention removed. Dirck haunts his own device. A spectral presence within a spectral presence.

I have issues with this precision, being that precision is an anathema to the concept of hauntology but can fully accept that Pepper’s Ghost marks the first physical commodification of the concept.

Hauntology, then, is a failure not only of the future, but a failure of the archive, with agoraphobia exacerbating that failure. Time’s Arrow flounders, trap within the archive, desperately attempting to free itself and re-establish the forward flow.

Recent Comments