Ley Lies

Map 1

1

All Mathematics would suggest

A steady straight line as the best,

But left and right alternately

Is consonant with history.

In his book How We Believe, Michael Shermer argues the human brain has evolved to be a pattern recognition engine. The patterns themselves are real but often subjective. The interpretations of these patterns are sometimes based on correctly perceived information and sometimes an attempt at imposing meaning on chance manifestations. I’ve mentioned this before in The Magic TV and others, but it is an idea that fascinates me.

The reason this ability has evolved is as an aid to survival. The recognition of patterns gives us valuable environmental information that allows us to make predictions about our current situation. It is a vital resource in our ability to learn.

Shermer asks us to consider the following scenarios:

False-positive: You hear a loud noise in the bushes. You assume it is a predator and run away. It was not a predator, but a powerful wind gust. Your cost for being incorrect is a little extra energy expenditure and false assumption.

False-negative: You hear a loud noise in the bushes, and you assume it is the wind. It is a hungry predator. Your cost for being wrong is your life.’

However, the need for this kind of pattern recognition has changed. Our modern lives are rarely concerned with predatory animals in bushes*, but we still see patterns everywhere. False positives and false negatives now have vastly different consequences for us. Obviously, we are not entirely free of predatory behaviours, so it retains some use, but I can’t remember the last time I hid from a lion on the mean streets of Portswood.

Shermer alerts us to these consequences calling them ‘pattern recognition errors.’ Such errors include such phenomena as seeing Jesus on a Dorito, seeing faces on the surface of Mars, ‘The Curse of Strictly,’ the vast majority of conspiracy theories and leylines.

I have to wonder whether this biological, evolutionary need to see patterns is in a state of evolutionary flux. Its use as a survival technique is no longer useful in the way it once was and through this need to find patterns, we’re applying this embedded ability to inappropriate situations.

For example, I first came across the concept of ley lines, more specifically Alfred Watkins concept of ‘The Old Straight Track’ in the sequel to Alan Garner’s ‘Weirdstone of Brisingamen’ called ‘The Moon of Gomrath.’ In it, to save his sister, Colin must find a specific plant that blooms only on one of these tracks. He sets off under the light of the full moon and sees an ancient pathway illuminated by the moon’s glow.

The endnotes in ‘Gomrath’ include a reference to Watkins’ book and, full of the magic of Gomrath, I set out to look for a copy of the book. It wasn’t anything even approximating the epic quest I had imagined as there was a copy in the library I spent most of my time in. It felt like a book that should be hard-earned, given the circumstances of discovering its existence, but there it was on the shelf, untouched for over 10 years.

There is undoubtedly a romance to the ideas contained in The Old Straight Track. The suggestion that all sacred spaces or places of interest can be joined in gridlike formations of straight lines hints at the presence of a real, supernatural presence. In my investigations, it seemed to lend credence to such things as dowsing and by extension, a plethora of other psychic phenomena.

I began to question the likelihood when I looked at a map of England that showed the locations of every church in the country. I cross-referenced this with ley hunter maps to discover that ‘holy places didn’t always intersect with ‘proven’ leys. Sometimes a point on the line could be hundreds of metres away from it, but it was always deemed to be ‘close enough.’ One of the reasons I liked the idea of leylines is that it apparently disproved the concept ‘there is no such thing as a straight line in nature.’ If that was the case, and a ley connected sacred features, the line should be straight and not fudged with kinks, near misses and ‘close enough.’

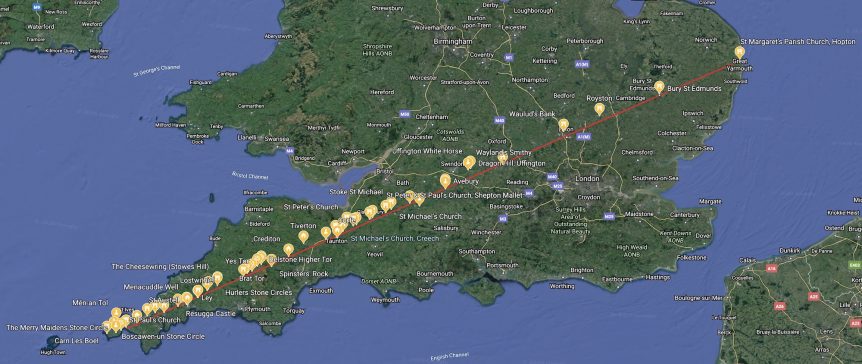

With common definitions insisting on the straightness of the line, the ‘proven’ ‘St Michael’s line’ as seen in map one, is woefully inadequate.

Map 2

Of course, looking at this map, the concentration of churches in the U.K. is so great that you could drop a ruler anywhere on it and find at least five or six sites that passed through – or ‘close enough’ to – the line.

Watkins’ initial inspiration for leys was in observing hilltops beacons, and how the towns in which these beacons reasted all ended with ‘-ley.’ There is little doubt the beacons formed a straight line, but the extrapolation into every site of historical or spiritual interest is something of a stretch. This well-meaning pattern recognition error has been taken up and expanded by new-age practitioners and pagans, giving the idea a life that was never intended.

I decided to map all the places I had lived to see if there was a pattern. As seen on map 2, they do fall roughly into two lines – with a lot of ‘close enoughs.’ There are one or two that don’t quite fit, but it could be argued that they form a third, minor line.

My ‘home leyline,’ if projected south, touches central Valencia (assuming one ignores the obvious straight line/ curved Earth problem that most ley hunters seem to). The cathedral holds what is thought to be The Holy Grail. The veracity of that claim, obviously, is in doubt. However, the vessel is deemed important enough to have been used for the inaugurations of many Popes. According to the tenets of ley hunting, I am connected to the power of the Holy Grail! This causes a ‘belief paradox’ in that ley hunters are performing an activity that is considered to be antithetical to the Christian religion, rendering Grail Power moot.

Map 3

The fact is that it takes very few points on a map to make a straight line, particularly if the ‘close enough’ rule comes into play. If you extend a line far enough, you will almost always hit a site of ‘greater significance.’

Looking back at Map 2, I should point out that is not really a map of churches, as stated. It is actually a map of the locations of Sainsbury’s supermarkets. Consumerist temples have as much to offer as spiritual ones in terms of ley lines, it seems. Currently, there are 1431 stores in the UK with a further 820 Sainsbury’s Local convenience stores and the map looks rather busy. Imagine twenty times as many dots on the map.

Given the concentration of points on Map 2, this raffirms that with enough points, you can make a multitude of straight lines. Finding a straight line is nothing special.

At this point, as a comparison, I was going to include ‘Map 4′ that would actually have shown the positions of all churches in the country. All 40, 300 of them. Google Maps couldn’t cope with the request. It was reluctant when I was simply asking for Christian spaces, but point blank refused when I expanded the search to all places of worship and sites of spiritual significance, modern churches, holy wells, tumuli, stone circles, burial mounds, etc.

Not finding a straight line would be an impossibility.

Ley lines appear to be a pattern recognition error of the highest order.

This actually annoys me as it’s such a marvellous, evocative idea. Even if it wasn’t Watkins intention.

Recent Comments