Melancholia and the Janus Hue – Part One

i

‘To attempt to write a guide to such an amorphous concept as melancholy is overwhelmingly impossible, such is the breadth and depth of the topic, the disciplinary territories, the disputes and the extensive creative outpourings. There is a tremendous sense of the infinite, like staring at stars or at a roomful of files, a daunting multitude. The approach is, therefore, to adopt the notion of constellations and to plot various points and co – ordinates, a ‘join – the – dots’ approach to exploration which seeks new combinations and sometimes unexpected juxtapositions.’ (Bowring)

Although specifically written about melancholy, Bowring’s outlook is one that I would apply to the entirety of hauntological study. It certainly applies to the four pillars, as discussed herein, but has a close association with melancholy owing to its relationship with the what I call ‘The Janus Hue.’ *

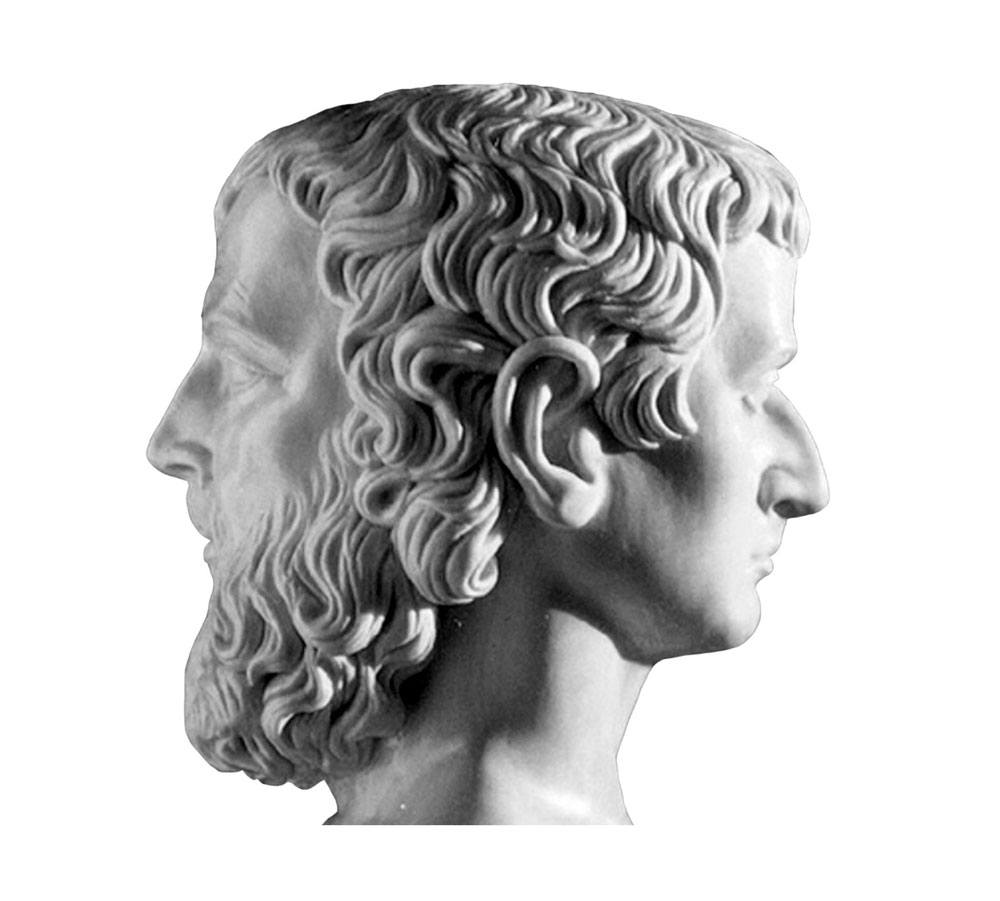

Janus is the Roman God of change and transition who represents time. His faces, he has two, look backwards to the past and forward to the future. His focus is never ‘today’ or ‘now.’

He considers the information from the past, finding patterns and omens in the information that has passed to project a favourable, possible future to those who seek his counsel. So important was he that each ritual performed by priests and clerics started with a blessing to Janus, regardless of which other God or Goddess was being petitioned. Janus, should you choose to believe in him, colours every aspect of our lives. To refine this metaphor, imagine a prism. Where usually a beam of white light is portrayed passing through the prism and splitting into its component colours, Janus takes the different colour information and processes it into a single white path.

Reinhart Koselleck suggested two categories of time: ‘The space of experience’ and ‘The horizon of expectation.’ (Kosseleck, 2004) Both are entirely subjective with ‘the space of experience’ offering a way of assimilating the past and rationalising it into the now. The space of experience is the past’s assimilation and manifesting as the present. The horizon of expectation allows for the present to extrapolate a variety of potential futures. It is the space between the faces of Janus and the manifestation of the creative imperative.

At this juncture between the past and the future, gateways – both physical and metaphorical – and progress, Janus represents the passage of time, rather than time itself which was the province of Saturn. Both have their aspects in melancholy. Janus by assimilating the entire past and processing the information to project new futures and Saturn lending his name to the word ‘saturnine’ meaning gloomy, miserable, brooding.

Melancholia, therefore, is a point on Times Arrow where all possibilities interact; a state of temporal liminality that leads to the one future not relished; the one future that was inevitable. Nothing changes and ‘get on with it’ is the resigned outcome. The melancholic mind will hold on to that moment before it slips through their fingers leaving them with exactly what they already had. Time’s Arrow resumes when one escapes from melancholy.

Janus is the now. He cannot see it, but he is the point on Time’s Arrow where we find ourselves at any given moment. He is the product of our past and the processor predicting our future.

Face-Brain-Face: Past-Present-Future

ii

Interlude One: In Kent, the roads towards the ports are filled with lorries. Where once a steady flow of traffic existed, the United Kingdom’s abandonment of the European ideal causes a massive influx of required information. This overwhelming influx has caused the previously steady flow to arrest, causing miles-long tailbacks. Once the required information is received and processed, the traffic moves on. The frustration and overwhelming data are processed. The temporally arrested lorries move forward with no discernible change from pre-Brexit checks. The lorries still make the same journey, but for this liminal space and temporal fracture, Kent is now a physical, geographical illustration of melancholy.

iii

Where nostalgia seeks to reclaim the past in order to move forward, melancholia is wholly accepting of the situation presented but gains no comfort from knowing these realities. Certainly, it can be difficult to distinguish between what Bowring calls the ‘of course’ response and the warm fuzziness of nostalgia. It is not even as simple as melancholy being ‘negative nostalgia,’ although that may be a trigger for melancholy.

The inevitability of events signals a resigned response. The past cannot save the melancholic and the retreat into nostalgia becomes both obstructive and destructive. One’s past remains in the past and offers no succour, cause and effect are suspended in favour of infinite ‘nows’ and the immediate arresting of Times Arrow before the burden of existentialism demands a dogged and stoic march through a state of ennui and into an unchanged future. The process is inherently pessimistic and hinges on the acceptance of the dry ‘of course’ moment.

As Bowring suggests, a universally accepted definition of melancholy does not – and cannot – exist. It may have achieved a kind of standardisation with dictionary definitions, but cold words fail to express the complex and often contradictory nature of a concept that is an object lesson in liminality.

Where one can wallow in the sense of nostalgia and thus feel better or healed from the rigours of the present, melancholia offers little but stagnation albeit typified by the promise of being swamped by a multitude of options. Their promise swirls around, taunting the melancholic with futures that may be, but settling on the least satisfying or most obvious – a dogged ‘get on with it.’

Of course.

No one seems to, or indeed can, fully understand melancholy and that makes it ripe for applying to states of liminality. The indefinable and the uncertain straddling the line between known and unknown.

iv

Melancholy has, at various times in history, been seen as a desirable state of being, an irritant, the mark of genius and a serious mental illness. It encompasses the full gamut of emotion. It is its own liminal state, neither one thing nor the other, a state in which all possibilities vie for attention.

Given that melancholy exists in a state of both solidity and ephemerality, being both desirable and detrimental, it occupies a particular liminal space where past and present collide in an overwhelming moment.

My own melancholia, as illustrated elsewhere on this blog, stems from an almost nomadic existence in my formative years. Without a solid base or a solid peer group, I find myself returning to old houses, old and familiar objects, not with any desire to recapture old glories, or enjoy the warmth of a nostalgic reunion with friends, but to acknowledge the inevitability of change within the stability of bricks and mortar; to trace my path and rationalise the present. Buildings are honest and do not judge.

Change is, perhaps, the only stability I knew.

These stories may seem, at least in part, nostalgic but I would claim that this is a more melancholic endeavour and about how I feel now. Revisiting a place forty years after leaving puts you in the position of having, through circumstance, an arrested perception of a given location. My Grimsby, (an upcoming post) for example, remained in the 1980’s, at least until revisiting. Coming face to face with of forty years of history led to the melancholic state of processing the glut of information presented by decades of history that have passed. Perhaps this is the cause of ‘post-holiday blues,’ so much new information to process. The disconnect between past and present is the onset of melancholy. Given that melancholy exists in a state of solidity and ephemerality, being both desirable and detrimental, it interrupts Time’s Arrow by creating a collision of pasts and presents in an overwhelming moment.

Recent Comments