Haunted Time – Haunted Space – Explorations of Hauntology, Agoraphobia and Time’s Arrow (Part Two)

VI

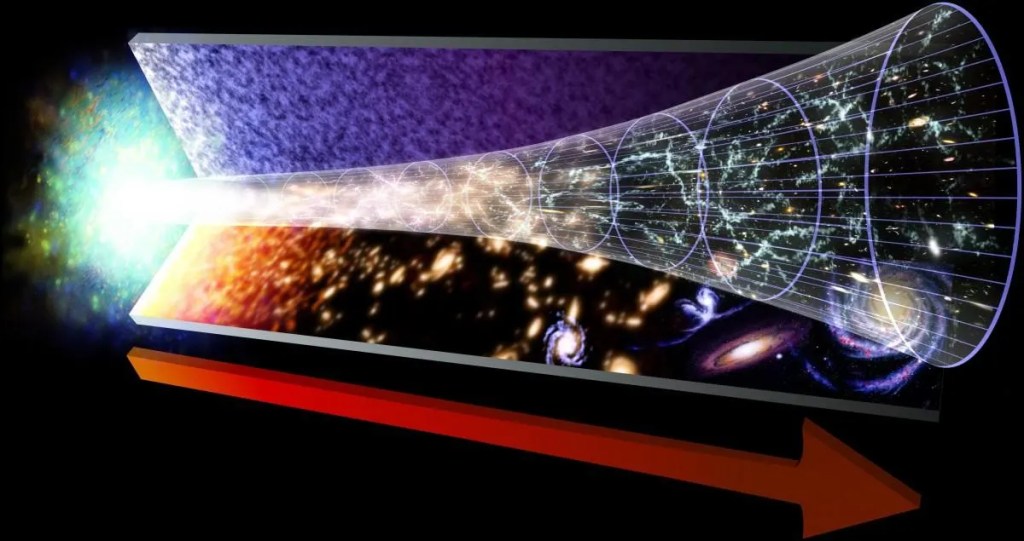

Originating in theoretical physics, the idea of ‘the arrow of time,’ or ‘Time’s Arrow’, is – I believe – pivotal to the idea of hauntology. More specifically, its disruption is intrinsic to how we perceive hauntological processes.

The theory gained popularity in 1928 with the publication of The Nature of the Physical World by Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington. In it, he muses that if we ‘…draw an arrow arbitrarily. If, as we follow the arrow, we find more and more of the random element in the state of the world, then the arrow is pointing towards the future; if the random element decreases, the arrow points towards the past.’

Although the concept of hauntology was not realised until almost seventy years later, along with Eddington’s assertation from the same essay that ‘the introduction of randomness is the only thing which cannot be undone’ are crucial to understanding hauntology. There are many threads to the concept of Times Arrow, thermodynamics, particle physics, quantum, weak force, and so on, but these have little to do with hauntology in any practical sense, so I will concentrate on the idea of the causal arrow of time with reference to the perceptual and to entropy. I do not particularly want to explore the science of Time’s Arrow here, as it is not so appropriate as the idea and its interpretations, but some of Eddington’s comments remain relevant to this study. For example, Eddington suggests that for Time’s Arrow to be, it has to be ‘vividly recognised by consciousness,’ that it is ‘equally insisted on by our reasoning faculty, which tells us that a reversal of the arrow would render the external world nonsensical’ and that ‘It makes no appearance in physical science except in the study of the organisation of a number of individuals.’

Eddington’s first comment is of note because it does not suggest a standardised and objective reality. Being ‘vividly recognised’ is open to a multitude of interpretations as is ‘equally insisted on by our reasoning faculty.’ These two statements offer entry to an entirely subjective mode of experience. Moreover, Eddington has allowed for infinite differing viewpoints in not stating solid parameters. What may be ‘vividly recognised’ at one stage of one’s life may not be so at a later moment. So it is with memory; what is recalled vividly in one moment may not be recalled later. What may be remembered vividly may not have happened at all but is subject to false memory.

As Alan Garner says: ‘We’ve only opted for the advancing linear flow, ‘The Arrow of Time ‘, because it’s the most efficient for our needs, and so the easiest to handle…’ (Garner, Boneland, 2012) but ‘efficient’ doesn’t always mean ‘complete,’ ‘true’ or ‘best,’ though. Garner’s comment suggests that there is much more to the passage of time than Time’s Arrow lets on, being subject to perceptual disruption.

In these terms, hauntology could be said to be an entirely subjective response to the disrupted passage of personal time. This disruption is entirely in keeping with Eddington’s assertion that Times Arrow is an indicator of entropy – that is, the progressive increase of the random element or the inevitable breaking down of order into chaos – a disruption of the carefully planned into an irretrievable state of breakdown.

Truth and reality become mutable and are secondary to the process of living. Within each of the explorations on this blog are the elements of a ‘new myth.’

Throughout, there is an element of exploring the possibilities of ‘Mythic Media,’ via ‘Mythic Time,’ that is, the time in which myths exist or are created. It is a confusing concept, not least because of its simplicity. It almost always refers to past events but is acknowledged to be as much of the ‘now’ and the future, as it is of the past. From that starting point, the inference can be made that mythic time does not conform to the idea of Time Arrow and wilfully ignores and perverts it; its job is to confuse and confound as much as it is to teach.

VII

Mythic time is divine time and does not exist in any linear time format. For example, in the Norse stories, Loki is both son and brother to Odin while being chained to a rock at the centre of the world for all time. (Crossley-Holland, 2018) Meanwhile, Ragnarök, the end of the Gods and of Asgard, is happening at all times. It is not cyclic but a permanent state of simultaneous birth and death. Similarly, the aboriginal state of ‘the Dreaming’ or ‘Everywhen’ is a time of myth in which archetypes, humanity, the animal kingdom, and heroic creatures coexist, geographies are shaped, skies are created, and the learned tell their tales. (Angus, 2012) Although The Dreaming is seen as a time of myth, it is also real, present and alive. Kemetism, a neo-pagan reconstruction of ancient Egyptian spirituality, also subscribes to mythic time as being of the then, the now and the always.

Mythic time lacks historical perspective and is not concerned with or related to history and historical development. It might contain fragments of real-time, but real-time is, as seen, entirely fluid depending on the observer. In contrast, ‘deep time,’ the time of geology, is always linear in format and obeys the historical perspective of temporality. From rigid to plastic, time is already a force that defies Eddington’s arrow. Its plasticity and malleability are perhaps what defines hauntology.

In his epigraph in Alan Garner’s ‘Treacle Walker,’ (Garner, Treacle Walker, 2022) Carlo Rovelli states, ‘chronological time is only one way of perceiving our world and not always the most useful one.’

Time is ignorance is quite an inflammatory phrase, suggesting that those who adhere to linear time know nothing. By extrapolation, those who have knowledge of time outside of time are truly the only people who understand its implications, its occulted information. In the same way, night and day are the only indicators of time passing in my temporally rarefied agoraphobic state, so in Treacle Walker, the only real indication of time passing is the sound of a train that passes his house at regular intervals.

Although the reality of Joseph Coppock’s situation in Treacle Walker is difficult to pin down, much like Susan’s exit from The Moon of Gomrath (Garner, The Moon of Gomrath, 1963), we are uncertain if his story happening as told, a fever dream, the transition between life and death, or tapping into mythic time – he appears to engage with a state of ever-present pasts, presents and futures.

This is the crux, the main thrust of Garner’s works: the mythic presence intruding into and blurring the perception of the present. In Garner’s works, the future is merely primed, ready for interpretation. His books never end with a neat and tidy resolution, just the idea that it has happened before and will inevitably happen again. This is particularly relevant to ‘The Owl Service’ (Garner, The Owl Service, 1967) in which a set of owl-themed crockery triggers a modern-day retelling of a tale from the Mabinogian (Gantz, 1976); Red Shift’ (Garner, Red Shift, 1973) in which a found arrowhead moves through three tales at different points in history. The inert object provides the thrust of the narrative. In these stories, time is cyclic, and myth evolves through repetition. In ‘A Fine Anger’, (Phillip, 1981), Neil Philip notes this recurrent theme in Garner’s work by saying, ‘Sequential, causal, ‘historical’ time is set against and enlarged by a ‘mythological’ concept of time as elastic, cyclic, recoverable.’

Mythic time appears to be a Mobius strip that surrounds Time’s Arrow.

This idea will be expanded on later and forms an important part of the perception of time through the filter of agoraphobia.

With mythic time having no specific start or end – even the Norse cycle that supposedly begins with Ginnungagap and ends with Ragnarök does so simultaneously – the events of the Norse gods did not have a specific order, timescale or location because Mythic Time – and thus mythic space – is non-specific. Unlike Time’s Arrow and its easy-to-understand ‘cause and effect’ model, events may occur out of sequence, backwards, simultaneously…

VIII

Time’s Arrow indicates – if not insists on – the existence of fate, an idea backed up by Fisher’s comment that ‘(fate) implies twisted forms of time and causality that are alien to ordinary perception.’ (Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie, 2016) Once again, Eddington’s comments regarding the nature of reality become pertinent. While ‘fate’ may appear to be a counterintuitive argument for what is essentially a case for a kind of proto-existentialism, Eddington’s thought experiment intimately and intrinsically demands that we, regardless of our attempts to change it, will ultimately succumb to the same end. That end is entropy, the breaking down and irretrievable dissolution of time, matter and dimension.

Time’s Arrow is an indicator of the rate of decay of the universe, and hauntology is the forlorn tool of doomed attempts at survival. At best, hauntology and its twisting effects on Time’s Arrow attempt to stave off the inevitability of an absolute end – a benign force of survival; it creates a new future or revives a past. It refuses the now in favour of something better, something alive – something that proves our existence.

And what, then, of death?

What of the moment when all potential futures end; all forward motion ceases? It is said that at death, one’s life flashes before one’s eyes. Is this the psyche’s last hurrah? A last desperate attempt at nostalgia, reminding you that life was worth living? Is it an attempt to elicit feelings of familiarity, safety, and warmth before the infinite dark and cold or a refusal to accept that entropy and death are inevitable?

In cosmic and existential terms, it hardly matters, but in personal terms, it indicates the existence of Thanatophobia.

Thanatophobia is a deep anxiety of death and dying. Freud would claim that this phobia is a result of childhood trauma, but to varying degrees, a fear of death is an inevitability to the living. (Freud, On Murder, Mourning and Melancholia, 2005) Named after the Greek god of death, Thanatos, Freud argues that individuals express a fear of death as a response to coping with unresolved childhood conflicts, although post-Freud, the ideas and vectors of the ‘death drive’ have been refined and remoulded. Fisher muses that ‘we are the blind slaves of the death drive, but, if we are not, it is because of an equally impersonal process: science, which consists in part of discovering and analysing the very processes that Freud calls Thanatos. The figure of the Radical Enlightenment scientist, then, is someone who understands the Thanatoidal nature of their own impulses, but who — precisely because they understand this — offers some possibility of escape from them.’

This hope – futile as it is – comes in the form of Thanatos’ counterpart, Eros. Thanatos, the death instinct, appears to be winning, as the life instinct reminds one of the joys of living, the joys of one’s own life, in a last-ditch attempt to stave off Thanatos’ terminal kiss, but Eros will – ultimately – always fail.

‘All life is merely a route to death,’ says Freud at his bleakest, inadvertently setting the wheels of existentialism in motion. But the parallels between Time’s Arrow, Hauntology, and Freud’s concept of the death drive cannot be ignored. If Time’s Arrow is the march of inevitability towards an ultimate death, its alliance with Thanatos, and therefore, the death drive is incontrovertible. The antithesis of this is the pull away from death, the drive to live, as represented by the processes of hauntology and the influence of Eros.

IX

‘I would read, of course, that in jail, one ends up by losing track of time. But this had never meant anything definite to me. I hadn’t grasped how days could be at once long and short . . . In fact, I never thought of days as such; only the words ‘yesterday ‘ and ‘tomorrow ‘ still kept some meaning.’

(Camus, L’Etranger, 1989)

Camus’ comment, as the incarcerated Mersault, illustrates the effects of the confusion of Time’s Arrow; the loss of temporal stability and an awareness that time ought to be passing. For the agoraphobia sufferer and Mersault, the antagonist in L’etranger, Time’s Arrow has been arrested. The processes of hauntology, agoraphobia and experience are, of course, entirely subjective, which makes qualifying and quantifying these experiences almost impossible, but Mersault provides a typically germane commentary: ‘I realised then that a man who had lived only one day could easily live for a hundred years in prison. He would have enough memories to keep him from being bored. In a way, it was an advantage.’ Certainly, this thesis would not have been written if my agoraphobic incarceration had not happened.

The ‘imprisoned’ aspect of agoraphobia suggests that the experienced ‘untime’ is exacerbated by being locked in with limited resources. For example, watching comforting old TV shows and movies, although still enjoyable, crushes me between the pillars of melancholy and nostalgia, thus diverting the direction of Time’s Arrow. The repetition of the past erases or obscures any potential present by filling the space where new experiences should be formed with wilful repetition. It reinforces the past by replaying old memories which, having been experienced recently, become new memories. The new/old memories confuse what constitutes ‘the now.’ It consumes those futures that can only be seen as filled with the past. Time’s Arrow has become a recursive trap that erodes self and self-recognition.

As time moves forward for the agoraphobic person, there are fewer new memories to juggle. With no new and significant memories to process, this becomes an exercise in mental entropy. Memories fragment and the past is broken down into the palatable and the non-palatable. The palatable overwhelms, and the non-palatable is lost. Some memories are inevitably lost in favour of more strident events. The world inside becomes a place of happy memories, making it all the more difficult to take that first step outside into a realm of lesser happiness and harmful memories, making the outside world a place of danger.

Nothing is ever simple, and everything comes with so many caveats that the only practical and realistic response is to fall into a state of inertia.

Interlude: Automata and Basinski

In the late 1970s and early 1980’s, the band Instant Automatons – part of the ‘weird noise’ genre whose raison d’etre was to provide original music for free, and without copyright restriction via duplicated cassette tapes – would end their live set with a tape loop echo. Often the phrase was simply ‘thank you and goodnight’ as they walked offstage, but this simple phrase would echo and repeat.

With each pass of the recording head, the recorded phrase would pick up another level of ‘atmosphere’ and audience murmur until the original phrase had fractured, distorted, and fragmented. A simple act of speech vividly illustrating the passage of time and the process of entropy.

Similarly, sound artist William Basinski presented a work entitled ‘The Disintegration Loops.’ This consisted of a series of recordings that he had made using shortwave radio, found sounds, etc., onto ferrite tapes. When he decided to digitise them, some twenty years later, he noticed that the tapes had deteriorated to such a degree that the act of playing them began to destroy the ferrite coating, causing the sounds to disintegrate with each pass.

Like William Basinski and the Instant Automatons work, repetition processes, destroys and reinforces the past. The difference is that it is the self that is being eroded.

In light of the ‘hundred years of prison’ quote from Mersault, it is interesting to note that my writing career started during my agoraphobic incarceration. Although I have always written, formalising my ability had never occurred to me until my perception of Time’s Arrow failed, until I was trapped with only the past and memories of the future for company. No surprise, then, that the majority of my creative work is based around nostalgia, memory, reminiscence, and the way the past infects the present.

In both cases, new information has been presented from the repetition and destruction of old information. The repetition supplies new information, an entropic process that tries to find nuance and new meaning in the recurring. It is a manifestation of the past that intrudes on the present repeatedly. It is becoming aware of structure through analysis or deconstruction, a fragment of something that can manifest in both tangible and intangible ways, a yearning for the impossible. It is discovering the flesh of the present by excavating the bones of the past, the sly insistence of an unwelcome repetition, an earworm, a serial intrusion of thought or experience, a memory you long to expunge but fear losing.

An existential crisis.

It is also none of these things.

IX

The main reason for exploring Agoraphobia via Times Arrow and Hauntology is as a method of reconciliation. Agoraphobia has caused me to live in a peculiar ‘untime’ where the path of my personal arrow of time has stalled or at least been stalled. I see the world move on without me and wonder what might be. I build futures that are impossible to achieve. I live vicariously through others’ achievements.

Being shut indoors for so long, my relationship with time has deteriorated. (‘Being shut indoors’ – a phrase that sounds quite benign compared to the confusion, frustration and anger agoraphobia induces.) I do not have the usual markers of time that I once had, with each day passing in the same uncatalogued manner with the markers of the ‘9 to 5 and into Weekends’ free routine. Days merge, and months merge. Days and nights as concepts still exist but are largely meaningless in the arrested flow of conceptual and perceptual time.

The boundaries between days, weeks, events, and celebrations have become unclear. Indistinct. The past, the present and possible futures clamour for equal attention, for equal and simultaneous billing. Time is out of joint, and tachypsychia becomes the norm: hours lengthening or contracting as the situation demands, or often at its own whim. Netflix and other streaming services add to the feeling of ‘untime,’ although this may be the product of being ‘of an age’ and a mild form of ‘future shock.’ With binge-watching becoming the norm – instead of a weekly instalment that demanded that you be in a certain space at a certain time – the regularity of the broadcasts became markers of the passage of time. Where a weekly broadcast that could be discussed, ruminated on and shared, consumption of TV media has become a race to see who can consume it first. The clamour for INFORMATION NOW is insatiable. This attitude seems alien and destructive. Accelerated consumption is of course, a marker of peak capitalism, but as previously stated, this is not my area of interest and Mark Fisher discusses this aspect in depth in his book ‘Capitalist Realism.’

X

It is intriguing that the main proponents of hauntology, including Mark Fisher, are all of a similar age, like me, spending their formative years in the 1970’s and 80s. All are subject to the same, or at least similar influences, including the rise of home video, the cinematic preoccupation with horror – specifically folk horror – the televisual treats of the Christmas ghost story and the traps caused by time. Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi adds to this idea by stating that ‘Born with Punk, the slow cancellation of the future got under way in the 1970s and 1980s…’ before noting the inherent absurdity of … ‘The idea that the future has disappeared is, of course, rather whimsical – since as I write these lines, the future hasn’t stopped unfolding,’ (Berardi, After the Future, 2011) and perhaps this is the main fracture and thrust in the idea of hauntology; the tension between a future that has failed but has simultaneously not yet happened.

It is interesting that Punk has become Berardi’s ‘year zero’ given the seismic cultural effect of the Sex Pistols appearing on Today1 with Bill Grundy. The future of the media and, indeed the psyche of the country, was irretrievably changed at the precise moment the dreaded ‘f’ word was spoken on live TV. Punk promised a new future of ‘no future,’ a disappointment with and disenfranchisement from everything the world had to offer. With the future exposed, anything went. People kicked against the ’no future’ mantra in an extraordinary explosion of creativity. The status quo was a thing of the past; the present not so much year zero, as ground zero.

Punk and post-punk music features heavily in Fisher’s work, particularly in ‘The Ghosts of My Life’ (Fisher, Ghost of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, 2014) that has entire chapters devoted to Joy Division, John Foxx, The Caretaker and let us not forget that Fisher’s website, where his writing’s on hauntology first appeared, was called ‘K-Punk’ and that the book is named after a lyric in ‘Ghosts’ by Japan.

I am not immune to punk, indeed, the album ‘Germ Free Adolescents’ has had a profound effect on my psyche. I hold Marion Eliot-Said, (a.k.a. ‘Poly Styrene’) up as a prophet of sorts, detailing the ills of the future world long before they came to pass.

Riding the zeitgeist, TV shows of the 1970s started to explore the disintegration of time and the inevitability of progress. ‘Raven’ is all but forgotten and involves a cave system with thirteen chambers aligned to the signs of the zodiac; once a guardian has been found for each chamber, the old knowledge will seep back into the new world bringing a new era of enlightenment. The Changes based on Peter Dickinson’s novels – The Weather Monger (1968), Heartsease (1969) and The Devils Children (1970) – collected as ‘The Changes: A Trilogy’ (Dickinson, 1991) – sees the ‘old ways’ arrest the development of the technological age by making any form of electronic equipment, or post-Industrial revolution machinery, unusable by spreading fear and anger at the very sight of it. Balance is restored once a placating visit to a cave takes place.

‘The Old Ways’ intruding on the modern era is the prime motivator for folk horror. One can’t help but wonder whether the sea change in the perception of time is what caused the sudden interest in ‘the old ways,’ as a form of neophobia.

Nostalgia is beckoning…

Recent Comments