A Psalm of Stone – Travels Around Avebury (Part One)

1

In 1977, ITV first broadcast a children’s TV drama – produced by HTV – called ‘Children of the Stones.’ Set in the Neolithic village of ‘Milbury,’ it told a tale of events that cycled throughout history, the mysterious powers that manifested inside the stone circle and the fates of the villagers that lived within said circle and came into contact with the Lord of the Manor.

As an impressionable thirteen-year-old, eager for supernatural thrills, I was utterly enthralled by the show. I wondered where the village of Milbury was but couldn’t find it in either our atlas or our AA road map. To me, this just added to the mystery and made the events of the TV seems more ‘real’; more exciting. It never occurred to me that the village – although obviously a real place – had been renamed for the purposes of the TV show.

During the unfolding of the drama, various named locations were visited and stories and myths about the individual stones were told. I absorbed and loved these stories, retelling them to my friends, none of whom watched the programme. It became part of my psyche in much the same way as Alan Garner’s novel ‘The Weirdstone of Brisingamen’ had a few years earlier.

I asked teachers, librarians and friends about stone circles and ley lines and none of them knew what they were or indeed what I was talking about. The consensus was that only one stone circle existed. That was Stonehenge and that it was built by the Druids. False on all counts. The circle I saw on TV therefore must have been a TV set. Disappointed, I stopped looking for the mythical Milbury circle unable to reconcile the aerial shots of the village inside the circle that was shown in the end credits of every episode.

Several years later, my friend Evan and I started chatting about old TV shows. He asked if I remembered ‘that weird thing with a stone circle’. I said I did and enthused about how fantastic the show was – and that I still had the novelisation and DVDs. After binge watching the entire series, he suggested we go and visit the site.

‘We can’t,’ I said, ‘Milbury doesn’t exist.’

‘No, but Avebury does,’ he said ‘That’s where they filmed it. It’s in Wiltshire.’

Feeling both foolish at missing the obvious name change and overwhelmed with excitement, we planned – poorly as it happened – a road trip. We borrowed a tent and some camping equipment from my friend’s neighbour downstairs, threw a few supplies in a rucksack and hitch-hiked to Avebury.

It took well over a day to get there. This was because the journey included being dropped in North London because the driver that picked us up decided to change his destination en route to Oxford. He refused to stop on the M1 to let us out. We ended up walking from Edgware to the outskirts of the Slough via Virginia Water – we were hopelessly lost.

2

The process of liminality within ritual space works like a chrysalis. One can enter into the liminal state, but on exiting, everything including one’s perception of the world is irrevocably changed. This is true even in profane – that is ‘not sacred’ – space. Like the chrysalis, you can’t ‘un-cocoon’ yourself to your previous state. The metaphor of cocooning and growth – or at least change – is analogous to the concept of ‘Chapel Perilous,’ first noted in Mallory’s ‘Morte D’Arthur.’

In Chapter 15, entitled ‘How Sir Launcelot came into the Chapel Perilous and gat there of a dead corpse a piece of the cloth and a sword,’ the sorceress Hellawes attempts to seduce Launcelot into an ungodly life. Launcelot is sent on a quest to find a piece of cloth and a sword that is housed in the Perilous Chapel. He enters and retrieves the artefacts, but on exiting, Hellawes is waiting for him. She tells Launcelot that if he leaves with the items, he will die. He refuses to give them up. Hellawes declares her love for him and asks for a single kiss. In exchange, she will allow him to leave with the sword and cloth. Launcelot denies her and leaves anyway. Hellawes had set the chapel up as an elaborate trap that Lancelot avoided because of his loyalty. Had he entered the chapel again after kissing Hellawes he would have met confusion, death and abandonment by God.

Chapel Perilous here acts as a symbolic Id. One of Freud’s three components of the psyche, the id is the impulsive part of our psyche that responds directly and immediately to basic urges and desires. The Chapel Perilous, via Hellawes, is offering base and libidinous gratification. Launcelot acts as the superego – which provides the moral standards by which the ego operates – in overcoming temptation and striving for perfection, in not allowing himself to behave in a way that contradicts the oath he has taken to Guinevere and God.

As a metaphor, Chapel Perilous lacks precision but when dealing with liminality, order and preciseness is difficult to impose because as soon as a solid definition is reached, the liminal state has passed.

Relph in (Relph, 2008) states that: ‘(Liminal) Space is amorphous and intangible and not an entity that can be directly analysed. Yet, however we feel or know or explain space, there is nearly always some associated sense of place.’ He further states that: ‘‘Existential’ space or ‘lived’ space… (is) intersubjective and hence amenable to all members of the group for they have been socialised according to a common set of experiences, signs and symbols.’

The Chapel Perilous as a psychological concept was popularised by and obtained some credence by counterculture ‘Quantum Psychologist’ Robert Anton Wilson. He defines the concept as ‘a psychological state in which an individual cannot be certain whether they have been aided or hindered by some force outside the realm of the natural world, or The concept of whether what appeared to be supernatural interference was a product of their own imagination.’

His description of the function of Chapel Perilous, wrapped in the language of ritual magic is thus:

‘Chapel Perilous, like the mysterious entity called ‘I,’ cannot be located in the space-time continuum; it is weightless, odourless, tasteless and undetectable by ordinary instruments. Indeed, like the Ego, it is even possible to deny that it is there. And yet, even more like the Ego, once you are inside it, there doesn’t seem to be any way to ever get out again, until you suddenly discover that it has been brought into existence by thought and does not exist outside thought. Everything you fear is waiting with slavering jaws in Chapel Perilous, but if you are armed with the wand of intuition, the cup of sympathy, the sword of reason, and the pentacle of valour, you will find there (the legends say) the Medicine of Metals, the Elixir of Life, the Philosopher’s Stone, True Wisdom and Perfect Happiness.’ (Wilson, RA., Cosmic Trigger.)

This reconfiguring of Chapel Perilous opens it up to the ‘ordinary’ person where once it was reserved solely for grail seekers, as seen above. With each psyche being unique, Chapel Perilous is by definition different for each person travelling through it; tailor made by the shape of the individual’s state of mind. Armed with a philosophical question, or dilemma, maybe an unfamiliar or potentially frightening course of action, a prayer, one will either:

Enter and come out the other side – although Wilson declares that this will result in either paranoia or agnosticism.

Enter and be consumed by confusion and run back to the front door, only to find it locked – one cannot enter Chapel Perilous and remain unchanged in Wilson’s model.

Enter and lose themselves forever.

Some travellers may stand at the door to the chapel unaware that the Chapel even exists, particularly if the metaphorical ‘wand of intuition’ is missing from the seekers psyche. The implication here is that one must prepare for one’s experience with navigating the Chapel. The unwary or unprepared visitor will be lost, but those with the above listed magical attributes, obtained through self-discipline, spirituality and learning will – as the Grail Knights – navigate the chapel and become illuminated or start on the path to apotheosis.

3

We got to Avebury at around midnight and pitched the tent. It was a black, moonless night, both characteristics enhanced by thick rain clouds. As we started to build the shelter, the clouds ditched their contents on us. Gleeful, relentless. Eventually, cold, wet, unhappy, we sat around a small Calor Gas stove. Neither of us wanted to eat, despite not having done so for at least 18 hours. This turned well as Evan had accidentally left the bag with the food in it somewhere along the journey. Probably at one of the service stations along the M4, if that’s where we had been. We couldn’t be sure.

It made matters worse, when we woke up after a freezing night huddling together to try and keep warm, that we were in approximately three inches of water. We had managed to pitch the tent in a depression that collected the rainwater.

I opened the tent. The rain had stopped, and sunlight was beginning to peek over the horizon. The landscape was covered in fragile mists and the discomfort of the previous six hours evaporated as we walked through the phantom swirls. We dismantled the tent, draining it of rainwater before packing it up and then went to the church. With it being so early, the shops and the pub weren’t open, so we had an hour or so to kill before we could grab anything to eat. The church provided shelter from the drizzle and was warm enough to cause us to steam dry.

I remembered from the TV show that the font had an interesting carving on it. It was suggested that some of the masons who worked on the church still acknowledged the ‘old religion’ and objected to the church being built at all, but work was work. As a cheeky nod to the old ways, a bishop was depicted being bitten on the foot by the ‘solar serpent’. Sure enough, just visible after centuries of wear and tear, a bishop can be seen.

Whether this story is true or whether the carving depicts the story – or part thereof – of St Patrick expelling the snakes from Ireland is up for debate but I like to think it is the former.

Buoyed by seeing the carving, which confirmed to me that Milbury really was Avebury, I suggested we search for some of the other sites from the TV show.

‘There’s a stone outside of the post office,’ I said, ‘It looks a bit like a cactus, but it’s meant to be one of the villagers holding her hands up.’

‘Oh, it that the one that was in the road? In the first episode?’ asked Evan.

‘That’s it. She owned the guest house that Adam and Matthew Brake move into.’

‘Totally freaked me out, that.’

I sniggered, ‘The whole thing was freaky!’

We walked to the post office and were deeply disappointed to discover that the stone was not there.

‘They can’t have moved it, surely? It’s a heritage site!’

The post-office also acted as a general store, so we entered to buy some food. Evan, who was always bolder than I, asked the post-mistress what had happened to the stone? She clicked her tongue.

‘Are you here just because of that bloody TV show?’.

‘Uh, no. We wanted to see the circle. I mean we liked the program, but…’

She made a harrumphing sound, ‘The stone doesn’t exist. It was a fibreglass prop. A lot of the stones were.’

Of course, it was. The same stone had appeared in two different places. How did we not spot that?

She snatched the money from us for some groceries and we slinked out, disappointed at the non-existence of the stone and at the rudeness of the post-mistress.

4

Ethnographer Arnold Van Gennep suggests that rites of passage follow a universal pattern consisting of three phases; the rites of separation, in which the neophyte is removed from his mundane life to the threshold of the new, elevated life he faces; the transition rites in which the neophyte sheds his previous life and travels facing the challenges of rebirth; and rites of incorporation in which he having traversed liminal space and partaken in the social constructs of ritual, takes his place within society, elevated and illuminated by his liminal experience. Van Gennep calls the middle phase the ‘liminal period’ and the subsequent incorporation the post-liminal period. All societies, he says, use rites to denote and demarcate important transitions.

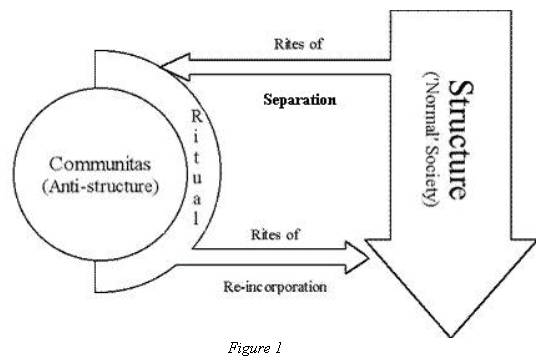

In Daniel Tutts model of liminal experience (below), we can again see the norm, represented as structure, and a rite or ritual as literally being outside of profane reality via Van Genneps Rite of Separation. Once again, the creation of a ‘bubble universe’ of sacred reality is constructed.

Anthropologically, the definition of liminality is ‘the quality of ambiguity or disorientation that occurs in the middle stage of rites’, ergo the state of being part way through a transition. The process of transformation takes place within liminal space and that transition once complete, manifests in post -liminal space and reintegration.

Liminality, therefore, operates as both the internal and external space of the initiate/participant and although there maybe a physical solidity to the place of transition – the lightless tunnel between the outside world and the Lascaux caves, for example – the spatial and psychological experience of the initiate, while sharing these spatial and temporal elements, is unique to each participant.

5

By this time, the National Trust Information Centre was open and we decided to get some more information about the site. We read about the history and the ways in which the site had been treated over the centuries with fascination. I was pleased – if pleased is the correct word – to hear that the story of the itinerant barber-surgeon, crushed under one of the stones – first heard by me in TV show – was true and that he met his end while participating in the now outlawed annual ritual of burying a stone for luck. In the light of the artificial stones, this made the TV show seem more real again.

As if to counter that feeling, on asking which stone had the solar serpent carved on it, the museum warden said, ‘Solar Serpent? There’s no stone with a serpent carved on it. Do you mean the font?’

I explained about the TV show and the carving.

‘Ah,’ she said, ‘I keep hearing about this programme, but I’ve never seen it. I think that stone must have been a prop.’

6

When considering the liminal, it is useful to remember that its root comes from the latin ‘limens’ meaning ‘threshold’ and liminal has come to mean something that dwells between two or more identifiable states. Thus, ritual space is neither of this realm nor of the divine or – the infernal – or their analogues, depending on the religious persuasion of the ritual observant – but a bridge between the three.

Ritual space – where the veil between the mundane and the transcendent is thin – is space that focuses ideas; lays bare the hopes fears and aspirations of the acolytes participating in a given ritual, that is, a series of actions and gestures used to communicate with the divine/infernal. Whether ritual achieves anything tangible is up to the interpretation of those who participate. Reality, and its interpretation, is in a state of flux. By nature of expectation, ritual space is liminal space. The liminality of ritual space acts as a buffer between three distinct paradigms – the divine, the infernal and the earthly – and occupies a specific, discrete area.

Many religions seek to give sacred space permanence by constructing buildings around them, Churches, Cathedrals, Synagogues, etc., but where sanctity refers to object and places that have been given special status in reference to the divine, liminal/ritual space is entirely non-tangible, ‘other’ and transient subset within a larger space.

Liminal spaces are places one visits as a break from the usual; places that exist outside of the norm and that represent a change, be it physical or non-physical (temporal, psychological, spatial); A discrete territory created on the boundary line of an established region. Ritual operates within all of these paradigms providing a temporary multisensory, multi-planar experience from which one emerges changed.

Rites of Passage, especially religion led Rites of Passage are particularly strong with the concepts of liminality and especially the concept of ‘Chapel Perilous’. As far back as the Classical Greece, the concept of liminality in terms of the spiritual were well known with neophytes being sent out to uncultivated mountains to have their status changed from the neophytic state to having full civic status. Odysseus, for example, was sent to the slopes of Mount Parnassus; Autolycus, his Grandfather, performing the ritual that elevated his neophyte status to manhood.

Cities, or Polis, were seen as areas devoted to particular Gods, each god having its own set of likes and dislikes; each city, believed to be discovered and founded by a patron god and gifted to humanity had complex rules and behaviours that were said to appease and displease. Although there is no one volume that explicitly states all of the rules and behaviours that are acceptable or not, Hesiod’s poem ‘Works and Days’ set out some of the rules and operates as a partial manual detailing the respect one should have for both nature and community.

Each instruction, such as:

‘Do not ever urinate in the waters of rivers flowing forth towards the sea, nor at springs, but avoid this especially—and do not shit there—for this is not better’

And

‘Do not ever pour fiery wine in libation to Zeus or the other immortals at dawn with hands unwashed, for they do not heed you, but they spit back your prayers’

And

‘If you are making a home, do not leave it unfinished, lest a cawing crow sit on it and croak’

are all ways in which an already sacred space, object or time – made so by the grace of a Patron God or Gods – can be sullied and made profane and unclean.

Living within a permanent sacred space would suggest that the Ancient Greeks lived in a state of permanent liminality. While this seems unlikely, one cannot deny that great advances in human knowledge were made under the supposed aegis of the Greek Patron Gods. As a non-liminal state existed only within prescribed areas of the city usually public latrines, and beyond the boundaries of the city and surrounding blessed landscapes -farms and slurry pits.

Hesiod suggests that tombs are not sacred – contrary to current belief – and warns against sitting ‘a twelve-year-old boy on what does not move (a tomb), (it is) a thing that makes a man unmanly, nor a twelve-month-old boy either, for this produces the same result.’ Whether this means more like a woman or more like the profane is unclear. I suspect the latter.

Ritual space within the polis/sacred space was only used in public displays for the establishing of a new community, or when introducing a new ritual, most often on the adoption of a new or imported Patron God.

Even further back, Stone age man understood the concept of liminal transitional space. Caves were certainly utilised for funerary rites and interment in the vast majority of Neolithic cultures according to Barnatt and Edmunds (Places Apart? Caves and Monuments in Neolithic and earlier Bronze Age Britain. Cambridge Archaeological journal.12(1) pp.113-129.) and traversing the passages leading to the funerary and ritual space – often in total darkness – was understood to be a transitional space between the profane and the sacred; the mundane world and the afterlife. These passages were likely viewed literally as portals to another world in the same way as creating symbolic ritual space is utilised today. As Bjorn Thomasson asserts, ‘Caves have been, in many cultures, crucial liminal spaces where shamanic ekstases occurred, bringing humans in contact with the spirits or the beyond.’ (Liminal Landscapes ch 2 p22)

Thomasson later states that the cave painting at Lascaux must be interpreted as being part of a ritual passage to the spirit world and a real liminal experience. This statement is based on Arnold Van Genneps ideas in ‘Rites of Passage’ on which he suggests a theoretical framework for explaining many cultural beliefs and rituals. He singles out rites of passage as special and separate from the temporal patterns of seasonal and group social change.

Shamanic experience tells us that ritual space is quite literally ‘the Shaman’ who acts as a conduit between the sacred and the profane. As such the sobriquet of ‘The Walker Between the Worlds’ is often used by neo-pagans. The Shaman is the physical embodiment of the threshold.

Recent Comments